BY RANDY LEWIS (This original article has paragraphs that have been omitted for context to opioid addiction)

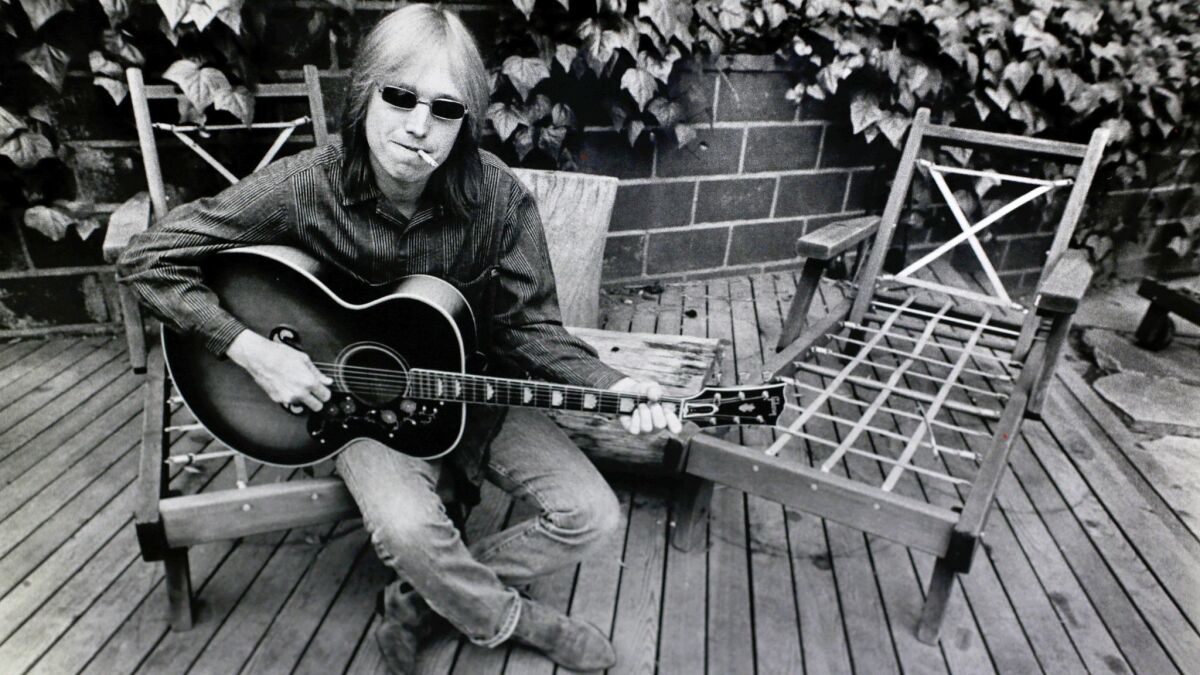

When Tom Petty was rushed to a hospital one year ago in full cardiac arrest, two words immediately sprang to many minds: Not again. Weeks later, the Los Angeles County Medical Examiner-Coroner’s report confirmed what many family members, friends and fans feared: Petty had accidentally overdosed.

Among the combination of sedatives, anti-depressants and pain killers found in Petty’s system was the opiod fentanyl, the same drug on which Prince overdosed in 2016. According to his wife, Dana, Petty endured the pain of a fractured hip throughout a 40th anniversary tour with his longtime band, the Heartbreakers.

“If he hadn’t gone on tour and [instead] had the hip replacement surgery, he would still be with us,” Dana said at the Malibu home she shared with the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame member, who finished up nearly six months of shows the week before he died.

Musicians who extend their careers into their 50s, 60s, 70s and even 80s confront physical aches and pains as much or more than the psychic and emotional wounds for which many have turned to substances — legal and illegal — for comfort.

The death of Prince, who had suffered pain for years and overdosed on fentanyl at age 57, raised questions that, with Petty, the music community has been forced to confront again: What might have been done differently? Will anything change in the wake of the latest death of a beloved artist? Are industry pressures a contributing factor?

Petty, then 66, slipped during a rehearsal and cracked his hip just as the Heartbreakers’ tour was getting under way last spring. He went out anyway.

“He was very stubborn,” Dana said. “His feeling was, ‘I can’t do that to my crew. I can’t do that to the fans. I can’t do that to my band.’”

On one level, the takeaway from Petty’s death is painfully simple. “The most important thing is taking care of your health,” said Elliot Roberts, Neil Young’s longtime manager who also once was part of Petty’s management team. “If you need to take six months or a year off until you’re ready to go out again, then take the time off.”

But that may be easier said than done, especially for musicians at Petty’s level of success on whom dozens, if not hundreds, of others are dependent for their livelihoods. Petty’s final tour grossed more than $61 million, according to the industry trade publication Billboard.

“I have arthritis, but when you get out there on stage there are endorphins and so many other things going on, my body can overcome the pain said fellow aging rocker Neil Young. Tom wanted to go out and play no matter what, and that’s the rock ‘n’ roll life, so God bless him. “But if you’ve got a busted hip, you probably shouldn’t be playing. The drugs just screw you up.”

The Recording Academy’s MusiCares philanthropic wing has placed clients seeking treatment at the Cumberland Heights center outside of Nashville. Chapman Sledge, the center’s chief medical officer, said that in recent years “the needle [on substance abuse] is moving — unfortunately it’s moving in a bad direction.”

Petty struggled with depression, anxiety and insomnia as well as pain from the hip fracture, as evidenced by substances the coroner found in his system when he died: fentanyl and oxycodone (painkillers); alprazolam (Xanax) and temazepam, (to treat anxiety and insomnia); and citalopram, an antidepressant. In addition, there were two non-prescription fentanyl analogs: acetyl fentanyl, a designer drug estimated to be five to 15 times more powerful than morphine, and despropionyl fentanyl, a synthetic analgesic about 80 times stronger than morphine.

“Two fentanyl analogs … that’s pretty scary, especially combined with the alprazolam and the antidepressant.”

MusiCares was established a quarter century ago to provide musicians in need with resources they may not be able to otherwise afford, including drug and alcohol treatment programs.

Rock music was born essentially 60-plus years ago, and the teens of the ’50s and ’60s are now part of the older generation. There’s a longer history for country, blues and jazz musicians performing and recording late in life.

“Dad is probably the best example out there of somebody who can have longevity in this business,” Lukas Nelson said of Willie Nelson, who continues to tour regularly at age 85. “I think keeping the right routine, keeping the right people around you [is crucial]. Making sure that your family is there to say: ‘Hey, quit that’ when something’s not good for you — and making sure you listen to them when they do.”

Willie Nelson did call off several shows this year after coming up short of breath during a concert in San Diego.

“He was sick; if he hadn’t canceled those dates, he would have died,” Lukas, 29, said. “He had pneumonia, and nobody knew. He just kept playing, just kept going, trying to push through this cold, and it turned into pneumonia.”

The physical demands of a career in music take their toll with age.

Performers who got used to racing around stages, leaping dramatically and dancing frenetically when they were in their physical prime discover that an exponential increase in aches and pains — and breaks and bruises — is part-and-parcel of touring.

Reflecting on Petty’s death, the Doors’ John Densmore said: “It’s too bad that Tom couldn’t let his vulnerability show like the great B.B. King, who sat in a chair playing the last several years of his life.”

Musicians in particular are much more aware today of the dangers of drugs — prescription and otherwise —than they were during the anything-goes mindset of the genre’s early days.

“When I started playing this music in the ‘60s, everybody did those kind of drugs: the Beatles, the Stones, Hendrix, up and down the block. We all did that. Take a walk outside your mind.” Tyler said. “Now, I just surround myself with people who know me. I’ve got good friends who ask me how things are, what I’m up to. We keep tabs on each other. It’s not easy being Tom Petty, being in pain, living the life he did. I loved the man.”

Densmore said the narrative needs to change.

“It used to be that whenever I was asked, ‘If Jim [Morrison] was around now, would he be clean and sober?’ I always used to say, ‘No, he was a kamikaze drunk and nothing would stop him,’ ” Densmore said. “But now we know about [Eric] Clapton cleaning up, and Eminem, who was a very angry guy, did his album called ‘Recovery.’ I’ve started to think, ‘Wait a minute — why not?’ For those kids who do have addiction problems, I want them to hear me say it’s cool to be clean and sober.”

South African singer, guitarist, songwriter Johnny Clegg, 65, booked a final tour of the U.S. last fall because he has pancreatic cancer and doesn’t know how long he will be able to continue performing. He said the energy boost he gets while on stage transcends the pain he experiences from the cancer and the chemotherapy treatments.

“I do the show, and then I pay the price a little bit afterward. But you know what? It’s the most amazing transformation,” Clegg said. “And I’d rather have my feet on fire for a bit after than the other way around.”

Follow @RandyLewis2 on Twitter.com

For Classic Rock coverage, join us on Facebook

Leave a Reply